From time to time, people get in touch with information connected to the music at Lichfield, and I was recently passed the following article written by Kerry Osbourne who was Clerk to the Governors of Bishop Vesey’s Grammar School in Sutton Coldfield from 1977 to 2016.

Jesse Flint is a name which I have not encountered in any of the Cathedral's records during my own research, but this account gives an intriguing record of a his possible connection with Lichfield. The contents of article is reproduced as submitted, but it has been formatted for easier reading on screen.

When I was approached with the suggestion that I should write an article for the Annual report of the Friends of Lichfield Cathedral my initial reaction was that I knew nothing about the Cathedral that would be of interest to the Friends. But then I recollected that in a book about Bishop Vesey’s Grammar School in Sutton Coldfield which I had written and published in 2000 there was an episode relating to the music master which referred to Lichfield Cathedral. The relevant extract from A History of Bishop Vesey’s Grammar School the Twentieth Century reads as follows:

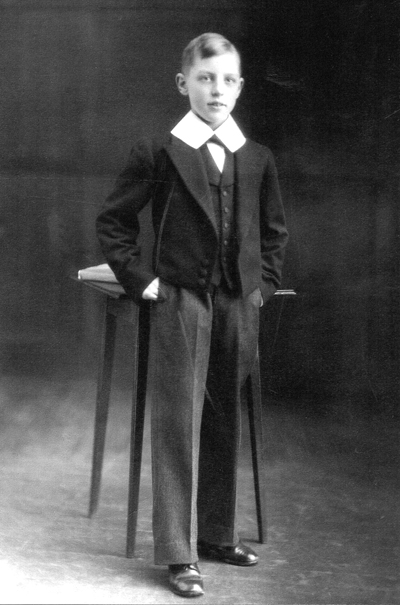

There was a Board of Education music inspection on 14 May 1915. This was a follow-up inspection to one twelve months earlier, which had been highly critical. According to the earlier report the standard of singing in the Third Form was no higher than should be expected in the First Form, as for piano teaching “the music in use appears to be somewhat old fashioned and inartistic and no valuable results are visible”, and the number of boys learning the piano was small in relation to the size of the School. There was no instrumental teaching. The second report concluded that little progress had been made. The singing of Rule Britannia is described as “unpleasant” and the method of teaching is criticised: “The boys never get a chance of singing until each song has been dissected for them with much talk. “Sing the first note”, -- “Sing the last note”, -- “Sing the note at the beginning of the second line”. After the song has been thus boned, the flabby remainder is handed to the boys to do what they like with, and it must be confessed that this is not much.” The music master, Jesse Flint, the organist at Lichfield Cathedral, was paid £18 a year and the Scholarship Committee advised the Governors “that at the salary now paid another Teacher cannot probably be found but in view of the fact that this is the second adverse report a change should if possible be made”. Mr Flint took the only honourable course open to him and resigned, probably without many regrets, and the Governors agreed a salary of up to £35 for his successor. There were twenty applicants for the vacancy, and despite a strong recommendation by one of the Governors Rev J H Richards, Vicar of Maney, for his church organist, H Graham Godfrey, the successful candidate was H Taylor, the organist of Edgbaston Parish Church at a salary of 24 guineas.

The story was almost scandalous; ‘Cathedral Organist Slated’ would be a modern headline. However, the first thing to do was to check that Jesse Flint was the Lichfield Cathedral organist, as he is described in Bishop Vesey’s Grammar School’s archives. The Cathedral has published lists of its organists and assistant organists; imagine my disappointment to find that the name Jesse Flint does not appear on either list! The post of Organist and Master of the Choristers (now known as the Director of Music) was held by John Browning Lott from 1881 to 1924, and the post of Assistant Organist (now known as the Cathedral Organist) was held by H. Rose from 1899 to 1911 and William H Harris from 1914 to 1919. The Cathedral’s list of Assistant Organists notes that a “gratuity of £10.10.0 was given to Mr Rose in recognition of his past services on 3 March 1911” which is presumed to be his leaving date. It seemed from the absence of Jesse Flint’s name from the official lists that there was, after all, no story worth proceeding with, and my inclination was to give up the proposed article.

However, second thoughts prevailed, as there were several intriguing aspects of the matter. Firstly, Flint must have told the Governors of Bishop Vesey’s Grammar School at least that he played the organ at Lichfield Cathedral; he was surely unlikely to tell them a downright untruth. Secondly, it will be seen that there is a period of three years between 1911 and 1914 when no Assistant Organist is named on the Cathedral’s list. It may, therefore be possible that Jesse Flint was called on from time to time to fill this vacancy, without having an official post; it is also likely that there was a rota of organists available to stand in at short notice in cases of holiday, illness or other emergency, and that Flint may have been on that rota. So perhaps, whilst not being “the organist at Lichfield Cathedral”, Flint was a recognised locum. Did he, then, exaggerate his connection to the cathedral when applying for the job at the school?

What else is known about Jesse Flint? He was born in Great Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, in about 1857. He studied at the College of Organists in London and was awarded an Associateship Diploma. The College was granted a royal charter in 1893 which entitled Associates to use the initials ARCO. In 1881 he was living at Woodhouse Eaves in Leicestershire, but by 1891 he had moved to Walsall in Staffordshire where he spent the rest of his life. He was the organist at St. George’s Church in Walsall (built 1875, demolished 1964) in the last decade of the nineteenth century. He was regularly mentioned in the Walsall Advertiser’s Gossip Column, for example: May 1894 – Mr Jesse Flint “the talented organist” directed the St. George’s choir in Mendelssohn’s Hear My Prayer. “It is Mr Flint’s aim to make the church noted for its musical services, which are of the cathedral type, with anthems at evensong.” August 1895 – “Jesse Flint takes infinite pains to present correct and expressive renderings of the works he undertakes.” He was also the conductor of the Walsall Orchestral Society (presumably an amateur orchestra). In 1899 he was appointed as organist at St John’s Church in Pleck, a parish of Walsall in the Lichfield diocese; after only two years the local newspaper reported that he was “presented with a handsome timepiece by the boys of the Pleck Church Choir as a mark of their esteem and affection”.

In 1902 Flint was appointed as a part-time music teacher at Bishop Vesey’s Grammar School; initially he taught singing one afternoon a week. In the same year he was initiated into the Wednesbury Masonic Lodge, giving as his occupation ‘Professor of Music’. He was not, of course, a professor in its usual sense of the holder of a chair at a university or college, but the Oxford English Dictionary gives another meaning to the word: “assumed as a grandiose title by professional teachers and exponents of various popular arts and sciences, as dancing, juggling, phrenology, etc.”, and cites a passage from Sir Richard Burton dated 1864: “The word Professor – now so desecrated in its use that we are most familiar with it in connection with dancing-schools, jugglers’ booths, and veterinary surgeries.” Flint’s use of the word in 1902 was therefore, at best, ‘grandiose’, but ‘misrepresentation’ seems nearer the mark, or ‘exaggeration’, to be charitable.

In 1907 the Governors of Bishop Vesey’s Grammar School issued a prospectus to raise the profile of the school, in which the Music Master is named as J. Flint, FRCO. Under the heading ‘Education’ the prospectus announces that Latin, English, French, History, Geography, Mathematics, Divinity, Drawing and Physical Exercises are taught throughout the school, that Natural Science (Chemistry, Physics and Biology) are taught in the four higher forms, that German and Greek may be substituted for some of these subjects, and, last and undoubtedly least, that Singing and Manual Work (i.e. carpentry) are taught to all boys in the lower part of the school. Under the heading ‘School Charges’ the prospectus mentions that the only, and purely voluntary, extras are £1.1.0. per term for instrumental music and £1.1.0. per term for dancing. A new prospectus was issued in 1911, by which time the school had been formally divided in to a Junior School (from the age of seven) and an Upper School (from the age of eleven); J. Flint, ARCO is named as one of the Junior School assistant masters (there are no mistresses) and class singing is listed as one of the Junior School subjects of instruction.

The initials FRCO stand for Fellow of the Royal College of Organists. Flint had the Associateship Diploma from the College, not the Fellowship Diploma. To become an ARCO a candidate has to demonstrate a high achievement in organ playing and supporting theoretical work; the Fellowship Diploma provides a progression for those who already hold the ARCO qualification and represents a premier standard in organ playing, which a cathedral organist would be expected to hold. Why then was Flint credited with the FRCO initials in the 1907 prospectus? Was it an innocent mistake or yet another ‘exaggeration’?

Jesse Flint had married in 1883, and there was one daughter of the marriage, Ethel Mary, born in Woodhouse Eaves the following year. She was a Pupil Teacher at the School of Art in Walsall in 1903 and she gained a Second Class Certificate in the Board of Education Examinations in 1906. She went on to be something of a celebrity in the local art world; some of her paintings can be seen at the New Art Gallery Walsall, one of which has the title ‘Corner of Lichfield Cathedral 1948’. She was also a council member of the Society of Staffordshire Artists. In September 1926 the Lichfield Mercury reported that she had given a special prize to the Lichfield Art School.

After leaving Bishop Vesey’s Grammar School Jesse Flint regularly advertised in the Walsall Observer and South Staffordshire Chronicle between 1916 and 1918. A typical advertisement reads: “Mr Jesse Flint ARCO etc. Hon. Local Examiner, Royal Academy and Royal College of Music. Organist and Choirmaster St John’s Pleck. Visits and Receives Pupils. Preparation for Examinations. Choirs Trained. Sutton visited. 94 Lichfield Street Walsall.” What is meant by ‘etc’ in this advertisement? If Flint had some other qualification, such as BMus, he would surely have specified it. Could this be another attempt to pull the wool? ‘Hon. Local Examiner’ is a bit puzzling as well. The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music (known as ABRSM since 2009) is an examination board founded in 1889. It provides graded exams and diploma qualifications in instrumental music and theory. In its first year it offered exams for five instruments: piano, organ, violin, cello and harp. Initially there were only two royal schools of music supported by the Associated Board, the Royal Academy of Music and the Royal College of Music; the Royal Northern College of Music and the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland joined the board in 1947. The present exam grades 1 to 8 were introduced in 1933; before that there were only two grades, equivalent to the present grades 5 and 6. Examinations are held throughout the country with professional local examiners. It might therefore have been more accurate for Flint to advertise himself as a Local Examiner for the Associated Board, rather than for the two named colleges. Another exaggeration? But the real oddity in Flint’s advertisement is the word ‘Hon’. Assuming that he was not claiming to be Honourable, he must have meant Honorary, which means unpaid. Is this an altruistic side to Flint’s character, not previously apparent?

It would be nice to be able to say that after the Bishop Vesey’s debacle Flint went on to have a long and successful career, but, alas, it was not to be; he collapsed and died “with painful suddenness” at St John’s Church Pleck in July 1918, aged 60.

I am conscious that there are gaps in my knowledge of Flint’s life, and it is difficult to assess his real character from the somewhat contradictory details mentioned in this article. If anyone can throw more light on the subject I shall be very pleased to hear from them.