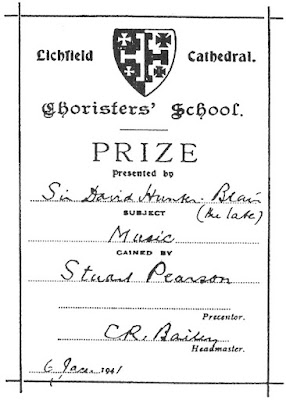

In sorting through some old papers, I found the 2003 copy of Lichfield Cathedral School's annual magazine. The edition included the following text written by former chorister, Stuart Pearson (born 1928), about his time in the choir from 1939-1941. It is reproduced in its entirety, with photographs, from the magazine.

I don’t know when the School was founded, but above the main

door of the School House wits carved the shield of the cross of St Chad, with

the motto, Serve God and Be Cheerful,

and the date 1912 (I think). This would no doubt be a reference to the date of

the building. The motto was adopted (at a later date) from that of Bishop

Hackett, Bishop of Lichfield 1662-9.

On Dam Street itself was a double-fronted dwelling known as

Choristers’ House, a Victorian building with three storeys and a basement. This

was the house of the Headmaster, Mr Bailey, and his wife, the Matron. It was

also home to the Boarders and to Lily the maid, and I think a cook.

There was accommodation for up to eight boarders, but when I

arrived on 9 September 1939, I made the numbers up to six. The dormitory was on

the top floor: one long room across the front of the house with bathrooms and

toilet at the rear.

|

The boarders outside Choristers' House, Easter 1940

from L to R: J E Dent, J S Dykes, J S Pearson, G J Wiseman, G N Burtt.

J Low (absent) |

We were summoned to meals by bells. The dining room was on

the left of the front door (the boys, of course, only ever used the back door);

it held a long mahogany table, with the Head sitting at one end and Mrs Bailey

at the other. There was one meal, I think lunch, a formal meal when Mrs Bailey

was present, where we only spoke when we were spoken to. We each had our own

places identified by our napkin rings, and the senior boys sat nearer the Head.

We were served by the hard-working maid Lily who brought up the food from the

basement kitchen and placed it before the Headmaster to serve.

Supper was informal and brought to us in our own playroom by

the senior boy. It always consisted of a plateful of thick slices of white

bread with jam or cheese and one knife with which to spread it. There was also

a huge jug of cocoa which we poured into our own mugs. As the food arrived we

would all cry out ‘fog [first] knife fog odd [piece of bread] fog spoon’ — not

that it made much difference because the bigger boys grabbed first and the

junior ones what was left!

School House

Behind Choristers’ House was the School, with a large gravel

yard in front of it. The form room was on the ground floor on the left of the

entrance, and the club - or recreation - room upstairs. The Headmaster’s study

was at the top of the stone stairs. There was a small cottage further down the

yard where one of the vergers lived with his wife. They looked after the

cleaning and heating of the School. At the bottom of the yard was a high wall

with a gate leading to the sports field and football pitch. It seemed always to

have sheep grazing on it. Alongside the field was the Headmaster’s allotment

which he attended assiduously, and which provided us with much of our fruit and

vegetables. The School was fairly basic but probably typical of its time, with

double-bench desks and seats, and blackboards and easels. There was the usual

teacher’s desk with a high stool. There was accommodation for between 20 and 24

boys but not all desks were occupied. We were all taught together by Mr Bailey,

who we called Boss, and the age range would be between 8 and 13 years.

Educational methods were very much based on the ‘three Rs’

and rote learning: we had to learn the times tables by heart, and repeat other

rules of arithmetic and English until we remembered them. So we did sums every

morning, and spelling tests, parsing sentences and writing stories. I don’t

remember algebra or geometry. I do remember Geography lessons with scrolled maps

of the world hung over easels and studying the areas coloured pink, but

recollect nothing of Art or drawing or even History. A large part of the school

day was, of course, given over to music.

The Music

I have recently

received, from the present Headmaster [Mr Peter Allwood], a leaflet describing

the Choir School of today and inviting applications from boys to attend a voice

test. The procedure seems to be much the same as I encountered in 1938. First,

I went with my parents to visit Mr Porter at his house for sight reading and an

ear test and then to sing a prepared piece of music. Later we visited Mr

Bailey, who asked about my education to date; I don’t remember sitting an

examination, as such, at that time.

It was a happy and proud day when we received a letter and a

Scholarship telling me that I could join the Cathedral Choir. Later there came

a list of items of clothing that would be required, which makes interesting

reading today. Best dress was an Eton suit with long trousers, and a deep Eton

collar with a black bow tie. Our everyday uniform was a dark blue blazer and

cap, both with the red badge of St Chad, and short trousers, together with

clothes and shoe brushes and sundry other items.

I sat in the choir stalls as a probationer for a week or so,

and then was robed fully (I have no recollection of a ceremony). Morning and Evening

Prayer were sung every day of the week, with the exception of Wednesday, which

was men’s voices only. Thursday was boys’ voices. I don’t remember servers

being much used at that time, nor was the ritual elaborate. There was always a

crucifer on Sundays and holy days, and that was Mr Bailey, our Headmaster, who

watched us continually for any misbehaviour!

There was no sung Matins on Saturdays: that morning was

spent in the Practice Room preparing for the Sunday services. But each morning,

after Assembly in school, we also marched, two by two up to the Practice Room

for an hour’s rehearsal before going across to the Cathedral for Morning

Service. The Practice Room was a light and airy room with a good acoustic,

having within it just two waist-high benches with an upright piano between and

at the head of them Mr Porter, Organist and Master of the Choristers, usually

stood at the piano so that he could see each boy. He could be quite fierce as I

remember, but singing for me was always a joy and not too difficult. In those

days, this room was, I think, situated down a lane between the house of the Custos,

Canon Kempson, and the Chancellor, Canon Stockwell. The Dean, The Very Revd F A

Iremonger, at that time lived at 9, The Close, the Deanery itself being, I

think, closed, no doubt a wartime economy.

The full choir consisted of nine boys on each side and three

adults singing each of the under parts, Alto, Tenor and Bass. As the war

progressed the boys became fewer and the adults also reduced in number. A Tenor

lay vicar, Mr Hall, was responsible for looking after the music and setting it

out before services. A senior chorister was asked to prepare the music on the

organ console for Mr Porter. During my last few months in the choir, that little

task was my responsibility. There was no official Deputy Organist as I

remember; we sang without a conductor, as was usual in those days. An Organist

would come in to deputise for Mr Porter from time to time. An interesting

feature of the choir of those days was that we were still using some manuscript

music, notably the chant book and some Victorian verse anthems and the Loosemore

Litany, which was regularly in use then.

|

| The choristers - four boarders and eight day boys - walking to the Cathedral for Evensong, Easter 1941 |

There were a number of memorable occasions during the years

I was in the choir. The choir was asked to broadcast Choral Evensong in 1940

and again in 1941. There were Ordination services each year, of course, and on

each occasion two choirboys were required to carry the robes of the Bishop. In

the course of time, this honour fell to me and my companion and we were given a

shilling each for our duties. I remember that Archbishop William Temple visited

his friend the Dean on a number of occasions. He always had time for the boys

and wrote in our autograph books. I remember a visit from Dr Walford Davies, of

Royal School of Church Music fame, and also a friend of the Dean. We were, I am

sure, warned that these dignitaries were coming, so that we were singing our

best. There were also Confirmation services, and on 19 March, 1941 three or four

of us were confirmed by Dr E S Woods, the Bishop of Lichfield, after very

thorough preparation by the Revd R L Hodson, the Precentor. We went to his

house in the south-west corner of The Close once a week for a whole term. We

seemed to take it all quite seriously; for instance, I kept the sequence of

notes that he gave to each of us for many years, and I still have the book of

private prayers called Before the Throne

which I found useful in later life.

It is hard to say, after 60 years, whether the standard of

singing at Lichfield in those days was as high as it is now. Perhaps the BBC

has a recording of our broadcasts in the 1940s for comparison. We always sang

without a conductor, being taught to listen and look at each other, as was the

custom. We certainly sang the typical cathedral repertoire of English church

music by composers from the sixteenth century onwards, and music from the

oratorios of Bach, Handel, Mendelssohn and Brahms. We sang, I think, one or two

complete oratorios for concerts, The

Creation, the Brahms Requiem and Messiah.

The School at War

The Second World War had begun just a week before my first

term started in September 1939, so many changes were taking place. The School

was affected in a number of ways. There was an assistant master on the staff in

the early days of the war, Mr Fox. He was a young man, a junior priest and a

minor canon, I think. He was great fun, and was responsible for PE and games,

and RE and French. But after maybe two terms he left us to take a parish or

become a Chaplain in the Services. He was not replaced.

Another change came to us at the School when it was decided,

no doubt by the Dean and Chapter, that for our safety we should not sleep on

the top floor of Choristers’ House, but in the cavernous cellars of St Mary’s

House. This change occurred during the second year of the war. So, some time in

the autumn of 1940 we began walking to the corner of Dam Street to the home of

Canon Cresswell and his wife and daughter each evening at about 8.00pm. The

situation was, of course, quite dangerous. We were very close to the bombing in

and around Coventry and Birmingham, and we could certainly hear the explosions from

bombs and gunfire and see the red skies in the West across Minster Pool as we

marched to our ‘air raid shelter’. Of course we all thought it was rather

exciting.

Food became more frugal (it was never lavish anyway) as

rationing was introduced early in the war, and identity cards and gas masks

were also issued. The windows of our clubroom upstairs were blacked out with

paint, I suppose because it was a cheaper option than curtains, but it made for

a gloomier existence. Most days after prayers the Headmaster would read out for

us the headline news from the morning paper, telling us about the air raids and

the number of bombers shot down and where our aircraft had been the previous

night, and about the naval losses. Occasionally he would read letters or tell us

of the exploits of former choristers who were in the Services. It was a very

sad day, especially for Mr and Mrs Bailey, when we were told of the death of

Flying Officer Jimmy Evans at the age of 21. He had been a very popular Head

Boy and had trained as a fighter pilot after enlisting when he was 18. At that

time, his parents still lived in Lichfield, and he had visited us at school

when on leave.

In our leisure time we were always scanning the sky on

hearing the sound of aircraft. Not far away, up the road to Burton on Trent,

there was an RAF training airfield, so there were lots of aircraft flying

around and we became quite good at recognising different types.

School Discipline

School discipline was tight, we thought, even by the

standards of the day. Boarders, for instance, were not allowed to go out of the

school grounds on their own at any time. Once a week we could go into the town

for shopping. It was always at lunchtime, for one hour only, usually on

Saturdays. Spending money was given to us on these occasions and we each had, I

think, sixpence. Typically, I would buy a Walls ice cream or a Mars Bar (3d), a

packet of foreign stamps or a comic newspaper. If we were late back, there was

trouble. Punishment was frequent for small misdeeds. It was always ‘spellings’,

i.e. writing out a difficult word 50, 100 or 200 times, such as ‘receive’ or ‘immediately’

or ‘maintenance’, to be handed in the following morning. There was also the

threat of the cane — a thick bamboo rod. This was reserved for really dreadful

crimes, such as scrumping. On one occasion about half a dozen of us climbed the

high wall of our next-door-neighbour’s orchard. Inevitably, we were seen and

reported, and caned, with a strong reprimand, by the Boss.

Leisure Time

Once or twice a month, if the weather was good, we were

allowed to go off for a walk, with the senior boy in charge. I remember walks

to the main railway line just north of Lichfield, to a footbridge where we

could watch the trains. Some of us recorded the names and numbers of the

engines. Another shorter walk was alongside Stowe Pool to St Chad’s church and

round the little hamlet there. Another walk was to the Clock Tower and the city

railway station, and on one or two occasions we were invited on to the

footplate of a small tank engine that was stationary for a time.

The highlight of our week was on Sunday afternoons when we

walked together to the home of Mr Spencer Madan. He lived in a gracious old

Victorian house with extensive gardens and parkland. I fancy that the house is

no longer there, but some of the grounds may be incorporated into the City

Park. The first hour or so we played games, cricket, croquet or football. If it

was wet, we went into the billiard room. Mr Madan would usually be with us and

would teach us the rules and how to play the various games. The second hour was

given over to reading in his study. He would choose the book and it was read by

the senior boy. I recall that we read lots of the Sherlock Holmes stories and

Rider Haggard books, as we sat in a semi-circle around the fire with Mr Madan

in the corner listening and interpreting where necessary.

Food aid was given to us, would you believe, on more than

one occasion. It happened like this. One of the vergers would wait for us to

pass on our way to Mr Madan’s house on Sunday afternoon, and tell us that on

our way back to school his wife would give us a boiled egg each. I t was very

much a cloak and dagger undertaking, and we were sworn to secrecy. The street

at the end of The Close passed along the rear of some small houses with windows

but no doors at pavement level. As we came by, the verger’s wife, whose name I

unfortunately can’t remember, reached out and put the eggs into our hands. We

ate them as soon as we could and enjoyed them enormously.

At teatime, two boys in turn were invited to stay at Mr

Madan’s house, while the others returned to Choristers’ House. Always, we had

delicately cut sandwiches and warm buttered scones, and importantly for us, we

could help ourselves to jam or honey! Spencer Madan would have been in his

seventies at that time. He was a tall, well-made man with a bald head, but he

walked with the aid of a stick to assist a very bad limp. He was probably a

veteran of the Boer War as there were old spears and rifles about the house and

Zulu memorabilia. He was also, or had been, an archer, as he showed us bows and

arrows from time to time. He was usually present in the Cathedral on Sunday

mornings, sitting in the same unnamed stall on the Decani side of the choir.

Going to Mr Madan’s house was acknowledged by all of us

boarders to be a wonderful treat. It was a visit that we looked forward to each

Sunday very much indeed. Before we could set off, however, on the short walk of

about half a mile, through The Close and up Beacon Hill, there was a little

hurdle to overcome. After lunch we returned to the school to learn the Collect

for the Day. Only when we could recite it to the Headmaster, each one

separately, and word-perfect, could we begin our treat!

Once a year a school party was held in the Bishop’s Palace.

This took the form, as I remember, of a mini-pantomime. A local entertainer, no

doubt, put together a show which was always great fun. On one of these

occasions I must have become too passionately involved when we all shouted out ‘Behind

you!’ or ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ to the Dame’s questions, so much so that I became quite

hoarse and unable to sing on the following day, Sunday. I sat down in the choir

stalls at one point instead of standing up, quite miserable and cross with

myself. Games Evenings were organised by the Headmaster from time to time. The

long winter evenings after prep were so boring. We did our best with stamp

collecting and arranging and playing cards, but resources were limited. I

remember that the Headmaster gave us chess lessons and taught us to play

cribbage and various games of patience.

The Closure of the

School

The end of the School, in 1941, came rather suddenly, it

seemed to us. We were not told very much about what was happening, as I

remember, just that there was not enough money to keep it open, and that

because of the War, teaching staff could not be found. 1941 was also the time

of Mr Bailey’s retirement. No doubt our parents were given the full reasons by

letter; I don’t recall a meeting. At the end of the summer term we said goodbye

to everyone. The four of us boarders certainly, and some of the junior day

boys, had a few years of treble singing left, as our voices had not broken; we

would most of us have been only 12 or 13 years old at that time.

Then there came for me an unforeseen development. I was

asked to come back in September, attend a day school in Lichfield and live with

the Dean and his housekeeper at 9, The Close. I still have no idea whose

initiative this was - the Dean’s or my parents’ - but I understood that if and

when a new Choir School was established, I should enrol and rejoin the choir.

When the new school opened, that did not, in fact, happen. I have happy

memories of living at number 9, however. So, after two terms on my own, I

returned home and attended a Grammar School near Huddersfield and continued

singing treble for another 18 months in the choir of Huddersfield Parish

Church.

Postscript

I returned to Lichfield in 1946 and attended some of the

events of the 750th Anniversary Festival held in June. I met again Mr and Mrs

Bailey, now living in retirement at 3 The Close, Mr Porter, and the Dean

(briefly). I kept in touch with Mr and Mrs Bailey and they were pleased to hear

that I was going forward to ordination. I last saw them in January 1955 when I

visited them at home in Norham-on-Tweed near Berwick. We had lunch together and

a warm conversation about the old days, and he took me to see the beautiful

parish church. We prayed together and he then told me that he remembered ‘his

boys’ every day. He was then in his 80th year, and failing in health. I did not

see them again.