|

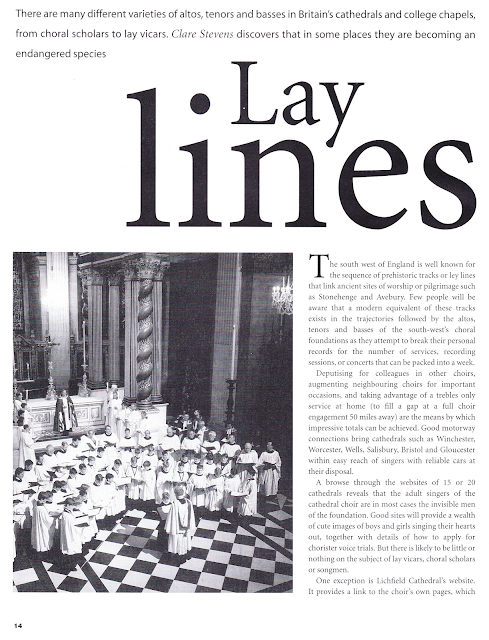

| Cover of 'Choir & Organ' January/February 2002 Never mind the choristers: Lichfield Vicars Choral have been around since 1241 Photo: The Earl of Lichfield |

The south west of England is well known for the sequence of prehistoric tracks or ley lines that link ancient sites of worship or pilgrimage such as Stonehenge and Avebury. Few people will be aware that a modern equivalent of these tracks exists in the trajectories followed by the altos, tenors and basses of the south-west’s choral foundations as they attempt to break their personal records for the number of services, recording sessions, or concerts that can be packed into a week.

Deputising for colleagues in other choirs, augmenting neighbouring choirs for important occasions, and taking advantage of a trebles only service at home (to fill a gap at a full choir engagement 50 miles away) are the means by which impressive totals can be achieved. Good motorway connections bring cathedrals such as Winchester, Worcester, Wells, Salisbury, Bristol and Gloucester within easy reach of singers with reliable cars at their disposal.

A browse through the websites of 15 or 20 cathedrals reveals that the adult singers of the cathedral choir are in most cases the invisible men of the foundation. Good sites will provide a wealth of cute images of boys and girls singing their hearts out, together with details of how to apply for chorister voice trials. But there is likely to be little or nothing on the subject of lay vicars, choral scholars or songmen.

One exception is Lichfield Cathedral’s website. It provides a link to the choir’s own pages, which include an explanation of how in 1241 the first statutes of the cathedral ordained that there should be a corporation of vicars choral, both laymen and priests, who would be responsible for singing the daily choir offices on behalf of the canons or prebendaries of the cathedral.

Today it is only at St Paul’s, Westminster Cathedral and Westminster Abbey in London that the gentlemen of the choir are all full-time professional singers. The contractual requirement at St Paul’s is to be present for 60 per cent of the statutory services during the course of the year, which allows them to augment their cathedral salaries by performing with other professional ensembles such as the Tanis Scholars, The Sixteen or The Cardinall’s Musick. But the basic salary at St Paul’s, which starts at £14,102 and increases on an incremental scale with seniority, is enough to live on, even in London, when combined with additional fees for extra events, special services, recordings, and tours.

Elsewhere it is a different story. ‘I suspect that only the London lay clerks have salaries that reach five figures: says Jeremy Filsell, who has recently taken up a post as an alto at St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, to complement his career as a freelance organist and pianist. ‘In most provincial establishments, the remuneration is very poor for the daily commitment required. Here we sing Evensong every day except Wednesday plus Mattins and Eucharist on Sundays, for a basic salary of less than £5,000.

But Windsor has the distinct advantage of having designated houses for lay clerks, dating from1430, which makes a big difference financially. A number of lay clerks here have property elsewhere that is rented out, and the housing also attracts the recently-turned-out-of-university choral scholar who may be “floating” to some extent while discovering his musical career direction.’

This is certainly the case at Wells, where lay vicars are accommodated in probably the most complete and certainly the most-photographed vicars’ close in the country. Lichfield also boasts an ancient vicars’ close but, says the cathedral organist Andrew Lumsden, only three vicars choral now live in it. ‘When they are appointed, the vicars choral are put at the top of the limiting list for accommodation in the whole cathedral close. They have been used to paying subsidised rent but the cathedral is gradually having to charge market rates, which are being phased in over several years.’

The men of the Abbey School Choir, who sing rip ‘weekday services in Tewkesbury Abbey, are accommodated in school flats that may be less picturesque than the residences of their colleagues in other choirs, but constitute an important incentive for recruiting new adult singers. ‘Their bills are paid, they can have their meals at the school, where most of them teach, and they are paid as though for an extra lesson for rehearsals and services, says Benjamin Nicholas, director of music at the Abbey School.

Teaching has always been the dominant profession of lay clerks in provincial cathedrals. ‘It is about the only job that will allow for the hours: says Andrew Lumsden. ‘But, he adds, ‘the teachers in my choir are having to take more time out than before for staff meetings and parents evenings and we are having to be more flexible in letting them have time off. I could stamp my foot and insist on 100 per cent attendance but it wouldn’t work and would only create a difficult working atmosphere. The men hate taking time out but they have to balance their “real job” with their “hobby”.’ Among the current lay vicars at Lichfield are a full-time student at Keele University and a manager for BHS. ‘I think he is on some sort of flexiworking. I don’t know how this works in practice but he rarely misses a service.’

Members of Southwell Minster choir have included in recent years two heads of music at comprehensives about 15 miles away, a freelance flute teacher, an artist/illustrator and a law lecturer at Nottingham University. Paul Hale, Rector Chori at Southall explains: ‘Because both their jobs and the quality of singing required of a lay clerk are more demanding than in the past, the pressure is acute. The larger or harder the repertoire, the better the man needs to be. The better a man is, the more professional a job he will have which makes it more difficult for him to attend at the required time every afternoon. ‘It was very different 60 years ago when the repertoire sung at each cathedral was much simpler and smaller and a lay clerk of no great ability could cope — thus he could be a piano tuner or a clerk and could come in more regularly.’

Hale acknowledges that compromises have had to be made to adapt to today’s circumstances. ‘Particularly with repertoire, where there simply isn’t the time to prepare the very hardest (generally 20th-century) material. We sing about 650 pieces though, which is pretty good repertoire by anyone’s standard, also with the standard of man I can employ and with the time I can expect them to arrive for rehearsal. Some simply cannot get here at 17.10 and come in over the next 15 minutes —hardly ideal, and not popular with those men who can get here on time.’

Jonathan Milton, who has just taken over the headship of Westminster Abbey Choir School, having been headmaster and also an alto lay clerk at Tewkesbury, emphasises that in the past plenty of Oxbridge choral scholars would become teachers in provincial cities, whereas now they either gravitate to a professional choir or ensemble in London, or to go into quite different professions.

While most of his contemporaries will continue singing at some level, Edward Parkinson, currently in his third year as an academical clerk at New College, Oxford, estimates that only around 35 per cent will aim to make a living from it.

As a scientist, finishing his chemistry lab work in time to get to Evensong has been one of the main difficulties he has experienced through combining singing with a non-musical subject. ‘The time commitment at New College is six 40-minute practices and six 50-minute services each week. With music preparation, a singing lesson and some practice it adds up to about 15 hours a week devoted to singing. This is really quite a lot compared to most other extra-curricular activities: Recordings, tours and concerts also eat into holiday time.

‘The choral scholarship is only £200, which is taken off our rent,’ continues Parkinson, ‘but the real perk is getting paid professional fees (Musicians’ Union minimum) for tours and recordings. This is a privilege which very few Oxbridge choral scholars enjoy. I think we probably earn £3,000 a year.

‘One has to be professional which is not something that students ever have to do. This can be hard to accept in the early days when everyone else is bonding and you have to sing Evensong: Parkinson had to abandon thoughts of getting involved in university sailing, but his colleague David Stuart found that rowing for the college’s first eight and running university societies was possible.

Both feel that any sacrifices are well worth it, because of the fantastic musical training they have received and countless memorable moments. ‘Singing the carol services in red cassocks in a packed candlelit chapel is one of the most Christmassy things I’ve ever done,’ says Parkinson. ‘We toured the Bach Christmas Oratorio around Germany in the snow and did a great French tour from the Pyrenees to Cannes where we sang an open air concert which was followed by fireworks.’

The majority of the candidates whom John Scott auditions each term for the deputies’ list at St Paul’s are fresh from college and university choirs and he sees little sign of the decline in numbers that is constantly being predicted. ‘Although the shortage of tenors is a worrying phenomenon, there would appear to be plenty of altos and basses. I am sure this is not reflected nationwide, but London is very much a singers’ town, it would seem.’

Paul Hale feels that salary and accommodation continue to be the two issues that affect recruitment of lay clerks. ‘The London cathedrals can always attract men without accommodation, and the poorest cathedrals rely on men on a smaller commitment singing for expenses only. It is the cathedrals in the middle group, spending between £70,000 and £150,000 on their music, that are the most vulnerable and the least likely to be able to pay well or offer free accommodation. It has become almost impossible for them to attract men.

‘Deputies are easier to find than committed lay clerks and one would desperately hope that cathedral choirs are not going to turn into large lists of men who are booked on a service-by-service basis. That way lies a lowering of musical standards and of the corporate spirit within a choir, which is the social and emotional glue bonding a choir together.’

In Andrew Lumsden’s opinion, the perception that the provinces are seen as a dead end for singers is another factor, ‘which is absolutely true, but there are other more worthy benefits than scraping a living in London. Fewer people are prepared to put in the time commitment and with dwindling congregations in parish churches and less singing in schools, fewer people know of cathedrals and their music.’

The positive side of being a lay clerk, Lumsden feels, is ‘the experience of singing some of the finest music in the world in one of the most beautiful buildings in the country on a regular basis. The sense of achievement when it all goes well on such limited rehearsal times is also very uplifting and the sense of teamwork and cameraderie is very compelling.’

From the other side of the choirstalls, Jeremy Filsell endorses this view. ‘It is very important for keyboard players to sing, and having spent a day practising Rachmaninov or Debussy, singing in chapel under someone like Jonathan Rees-Williams is a wonderful musical “foil”. Contributing to something inspirational and spiritual, knowing that one is part of a long succession of those who have sung and played music ad majorem Dei gloriam in such extraordinary surroundings since 1378, and the notion that this is all something “more important than thou” is a genuine privilege.’